800 days to save Stoke

800 days to save Stoke

Liz Truss’ victory as Conservative Party leader suggests a change of direction for the Government. With a renewed and vigorous pursuit of national economic growth, the policy priorities of the Johnson administration are now in doubt - none more so than the flagship ‘levelling up’ commitment. Despite a stated commitment to levelling up in her leadership campaign, her approach will differ radically from Boris Johnson’s. Rather than highly-targeted, hyper-local spending to boost towns, it seems likely Liz Truss will focus on the development of investment zones, regional tax cuts and other supply-side measures to boost growth. This might pay off in time, but the risk is she is seen to abandon levelling up just as voters come to understand and like the idea.

Such a strategy is risky; given evidence that the policy has finally cut through with the public, rowing back could weaken Truss’ electoral coalition. Public First polling for the Centre for Policy Studies recently revealed how committed working-class voters are to Boris Johnson’s levelling up strategy; many are leaving the Conservative Party because of a sense their families and their towns have been let down as the economy deteriorates. For Truss to be successful, her measures must allow a rapid reverse in high street decline – and deal with some of the public service challenges, including crime and skills, that people notice.

The Conservative triumph in the 2019 General Election saw the party win seats in Labour heartlands across the Midlands and North. Constituencies like Stoke-on-Trent Central, which had never returned a Conservative MP, became symbolic of this electoral shift. The Brexit gridlock, a distrust of Jeremy Corbyn and his Labour Party, and a belief Boris Johnson would deliver real change for them led many to vote Conservative for the first time in their lives. Despite the promises of change in 2019, the phrase ‘levelling up’ was a phrase few outside of Westminster had heard. Now, almost three years on and 800 days out from the next election, we find that has all changed. Not only are the public familiar with levelling up, they think it’s the right policy to pursue - and can often recall specific promises the Government made to improve their area. Increasingly, they are growing frustrated at a perceived lack of progress. Meanwhile the Labour Party, determined to win back their lost seats, have swung behind the policy (if not the name), launching their own pitch on how they can regenerate left behind areas of the country.

In this new report, Public First set out to understand what the administration must focus on to ensure they don’t lose the progress on levelling up their fragile electoral coalition expects them to deliver. But we also looked at what levelling up policies the Labour Party must champion if they are serious about winning back their lost seats.

For our research case study, we selected Stoke. Not only is the city an example of a traditional Labour stronghold which is now Tory-held - with the Government focusing much of its levelling up narrative on the city - but the cost-of-living crisis is expected to make people in Stoke among the most fuel poor in the country (as we print this report, the government has announced new, substantial, support on energy bills). This really matters given massive public concern about rising energy bills; in focus groups conducted recently, we have had people weeping through fear about how they will pay their bills.

To understand how the people here felt, and what they wanted to see from the new Government, we immersed ourselves in the city. Instead of focus group research, we spent time with people in more natural settings, and for a longer period of time. This is something Public First will engage in increasingly in the future; we have found this immersive research to open up a new dimension in political qualitative research. Listening to residents in their places of work and leisure, their homes, their shops, and on their high streets, our deep dive research offers a depth of understanding, and level of detail, which is difficult to gather from more typical research methods.

You can read the full methodology here:

The working class of a proud city

Ten regulars were sat together in an otherwise empty pub in an overcast Burslem; an assorted mix of ages, some long retired, others wandering in from their work shifts. “There used to be thirteen pubs on this strip" the manager recalled while pouring a round of the local Bass ale; “now there are just three”.

Clearly comfortable in their own silence, the conversation was eventually kick-started by a younger man asking the oldest on the table about his time working as a miner. He gladly accepted the invitation to reminisce. His companions, too young to have experienced the mines themselves, nodded approvingly as they listened to his well-thumbed stories.

Stoke is an unique place. Without a central high street or ‘city centre’, the Staffordshire city is made up of six towns: Stoke-upon-Trent, Hanley, Burslem, Fenton, Longton and Tunstall. Traditionally the potteries were the main source of employment in the area, the rich history of clay and coal excavation remaining a major source of local pride to this day.

Work is deeply important to people in Stoke; it’s integral to the identity of the city. The group in the pub talked glowingly of the city’s glory days of industry. Everyone had a relative or acquaintance who used to work in the potteries or in the mines. That pride in their craft remained. Smiling, one man who worked as a roofer reached out his arms to display his well-worn thumbs. Others talked proudly of their many years in their respective trades. Stoke is an authentic working-class city in the genuine sense of the term.

People know there are deep, underlying social and economic problems in Stoke. ‘Deprived’ rolled off their tongues when asked to describe the area where they lived. But this was a well-worn badge, and people here showed a strong sense of resilience to the area’s troubles. They were used to it. As a man in a shop in Hanley explained in a matter-of-fact tone:

“People aren’t poorer in Stoke than other places round here. It’s all poor; it’s not significantly better anywhere else.”

The view of Stoke as a deprived area wasn’t a universal one. A taxi driver, who had lived in Stoke his entire life, refused to hear criticism of the city. Taking great pride in being from the area, he was keen to note how friendly the people are, the geographical benefits of its location, and the affordable housing on offer.

“It’s [Stoke] perfect, not too busy, not too quiet, the people are nice. Yes, there are issues with drugs but that is everywhere - in Preston, Liverpool etc … The house prices here are reasonable; compared to other cities it’s so much cheaper … there are jobs, if you go to the job centre- there are thousands of jobs.”

The sense of local community was clear. A restaurant owner in the centre of Hanley made sure he greeted every customer personally. He explained that he knew all the people who came into his diner and how, in the twenty-five years he had run the business, he had grown it despite other shops in the area dwindling.

“I know pretty much everyone here; they are all regulars; I’ve known them for years … There are so many other shops that have been shutting down.”

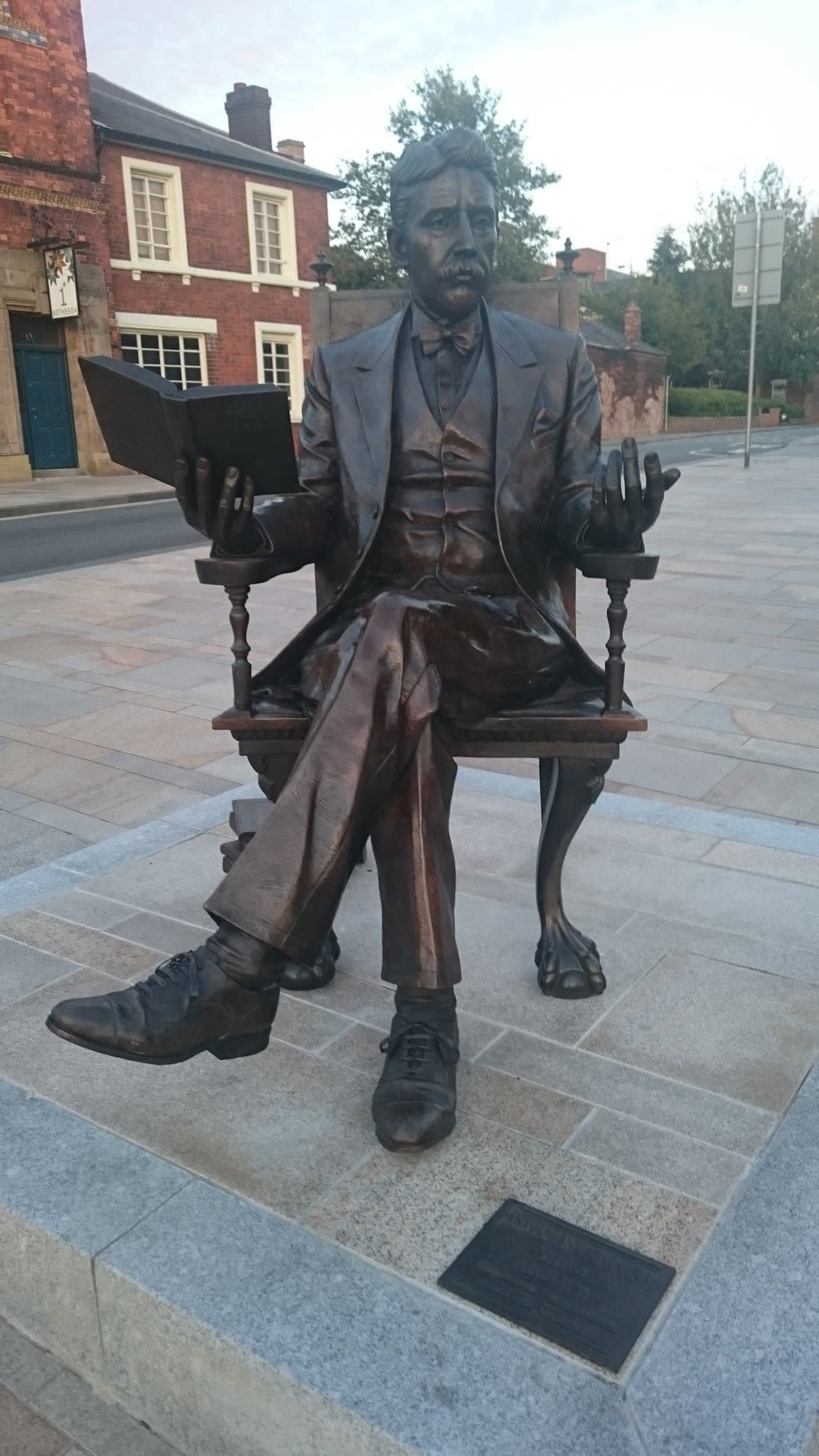

People’s relationships with each other and the city they shared also extended to its past. A particularly welcoming man in a charity shop in Hanley was delighted to talk about “his” city, and fondly handed over its most famous literary work: Anna And The Five Towns, by Arnold Bennett; Bennett’s gifts and success were great sources of local pride. Bennett is one of Stoke’s favourite sons, and his legacy is deeply felt.

“Go see the statue at the end of this street; Arnold Bennett is sitting down. He is sitting down because he was not above the people of Stoke.”

Joining a retired couple for a cup of tea in Burslem, they too boasted of Arnold Bennett. The man delightedly mentioned that his wife had been named Anna after the book and announced that they were planning to freshen up his plaque in the centre of town with a bucket of soapy water over the weekend.

The younger people we encountered were less enthused about the history of Stoke but found other sources of pride in the city. One young man, initially from Essex, who had moved to the city for university ten years ago and never left, explained that nowhere else would he be able to afford his own home, before pausing to point out the wealth of green spaces in the city.

The research was undertaken the week before A level results day. Several of the city’s younger residents were nervously awaiting their grades. Joining a youth centre for 18–25-year-olds on the outskirts of Hanley to take part in their evening meeting, the tone, when asked about Stoke, was warm. They sat joking about the city and its problems, but when asked, all wanted to stay local and study, with the University of Staffordshire in particular a destination of choice.

The perception of a city in decline

In the kitchen of a café tucked away on a side street in Burslem, two women made breakfast for a small cohort of loyal customers. Over scrambled eggs, they explained how the town had changed over the last few decades.

The closure of the potteries has had a major and lasting impact on the city. Unemployment rates have consistently averaged above both the regional and national rates, while in some areas of the city up to two-thirds of children are estimated to be living in poverty.

It was the decline of their high street which was perhaps most sorely felt. The evidence of decay surrounding the café was unavoidable. A glance up and down the street yielded boarded-up shops covered in graffiti, and a discarded sofa resting on the pavement. People here still had a strong emotive vision of what the town used to look like. As one of the women explained, the closing down of industry had taken footfall with it, making it very difficult for any new business to open.

“All these shops around here that are boarded up were open before. They are all beautiful buildings … Burslem needs a facelift; they don’t care about the town. It used to be the mother town of Stoke. I’ve seen it at its best and now at its worst. There’s no council investment. Businesses are opening but failing to thrive. There’s no footfall. The Daltons factory closed. My stepdad worked there. The footfall from that just went when it closed ... it was years ago, but we still feel it.”

Frustration at the state of their town centres was universal. People in Stoke shared a memory of a time when people would regularly visit the towns, particularly Hanley, for shopping or a night out. Those days were long gone.

“Everyone used to go to Hanley; my mum and nana would go shopping there all the time. They don’t go there anymore.”

The idea of regenerating the high street was not new here. People were aware of the promises that had been made to their communities. One woman rolled her eyes when the conversation turned to levelling up, and the idea that investment might help bring life back into her high street.

“I moved out of Hanley; all this regeneration that was promised, it never happened. It’s not safe after dark to go out, I just had enough. I’ve moved out the towns.”

For many, the decline of their high streets was driven by the rise in crime and drug use. Outside the Post Office in Burslem people moved quickly, afraid to loiter too long on the high street. As one retired woman explained, looking over her shoulder, there was nowhere else safe to withdraw cash:

“All the banks have closed. This is the only safe place to get money out. My mates have been robbed at the cash point, one had £400 nicked.”

Crime and the corrosive impact of ‘monkey dust’ (the local slang for spice) was not far from anyone’s lips. A young woman in a shop in Hanley confirmed how the last few years had brought with them a vast reduction in footfall, with the benches on the town centre now full of drug users. She saw crime and low-level anti-social behaviour as the key reason people were no longer visiting the high street. This, she concluded, was a result of the lack of police presence in the city.

“They’re all on monkey dust. We need more police; there are drug dealers on the streets in broad daylight, literally right now. No-one is doing anything about it. It didn’t use to be like this."

While most agreed more police were required to keep people safe and clear up the high streets, others were keen to point out that the very visible drug use – as well as homelessness - was also down to a lack of investment in the city. As the Arnold Bennett enthusiast in the charity shop explained, people here were getting no help. He wanted to see investment in the form of new house building but had no faith the Government were serious in their commitments to the area.

“Stoke needs investment and places for people to live. Down this street, have you seen the tent with the toys for the school holidays? That’s for kids to play in during the day, but people sleep there at night. How is that right?”

This view was shared by the retired couple in Burslem, who agreed Stoke was no longer the place that their hero once wrote about.

“I think Arnold Bennett would have a shock if he saw it [Burslem] now. The very house where he was from is now a doss house.”

Across the city, there was little sense that much was being done to halt the decline and deliver meaningful change. The pub regulars in Burslem bemoaned what was happening to their city. For them, Stoke had been deprived since the potteries closed, with so many businesses and venues folding in the aftermath.

Importantly, the investment they were seeing was not what they expected, and what new buildings did spring up, they were not proud of. It certainly, to them, was not evidence of levelling up. They were particularly scathing over the new hotel developments, which in their eyes were doing nothing to help the areas where they lived.

“I don’t think there are more places in the country with shut-down places than Stoke.”

The youth centre staff in Hanley shared the same frustrations; they believed the focus on car parks and hotels was of secondary importance when so many shops on the high street remained empty.

“Look at the money they have spent: why bloody car parks? We don’t need another car park; there are so many empty shops.”

While for those running their own businesses, there was little belief that the Government was doing all it could to support them. For the restaurant owner in Hanley, high business rates were a barrier to new shops opening on the high street, and the Government seemed to be in no rush to turn things round.

“They need to drop the business rates. The big shops are closing down and nothing is replacing them, because business rates are too high … I pay £200 a week business rates, that’s before you add VAT, insurance etc.”

A city with few options

A young apprentice in the salon hovered as customers’ nails were treated, chatting amiably with her boss. Both were happy to discuss what life was like for young people in Stoke. The question of what young people do for leisure was received with mild amusement. Handing over a cup of tea, the apprentice explained that youth centres were unable to offer anything appropriate for people of her age; even the one which purported to do so was oversubscribed with young parents and their children.

“There is a youth centre; it’s meant to be for people my age but it’s just full of crying kids, so we don’t go there. We just sit in the park and do stupid stuff.”

Later that evening in one of the more upmarket restaurants in the city, when asked for recommendations of where to go for drinks, the teenage server was less than enthusiastic about what the city had to offer. Later, a young woman expressed the same sentiment, suggesting that young people were better off heading to other cities for a night out.

“Young people go out in Liverpool; there is nothing going on here. There’s a bit of a strip in Hanley but that’s it; there’s nothing for young people here.”

For a city obsessed with its past, it was perhaps young people and the career opportunities available to them which drew most debate when considering where the city most needed levelling-up investment.

Some in Stoke were critical of younger people, arguing that they lacked the work ethic of previous generations. An older man, who ran a shop in one of the most deprived towns, remarked while rolling his eyes “jobs are there for young people, they are just too lazy”. But there was sympathy for them too. At a youth centre in the city, the staff talked about how difficult it was for young people to get work in the city.

“Unless you’ve got an education it’s difficult as a young person. In Stoke seventy per cent of young people are in work or education, so thirty per cent of young people are left behind.”

People wanted to see Government investing in places for young people to go. Even those who criticised their work effort were starkly aware that the youth of today lacked physical spaces of their own. This was echoed by the café workers in Burslem, who looked visibly downtrodden when asked to consider what life was like for young people in the area.

“I don’t think there have ever been job opportunities for young people here; there are no youth clubs. Young people here literally are inbetweeners, they have nothing to do.”

Resolutely, while refilling cups of tea, the café worker argued that the Government should consider schemes to help young people in to work - praising apprenticeships, and initiatives that had helped her in the past:

“I think apprenticeships would make a big difference. Bring back the YTS [youth training scheme]. The Government covered your wages. I tried hairdressing. If you were lucky, they would keep you on after two years. It wasn’t for me but at least I got to try it.”

While in the charity shop in Hanley, the idea of career opportunities for young people was met with scorn. He was quick to sympathise with young people, pointing across the road to one of the few independent shops left on the high street and arguing if they were very lucky that was the best they could realistically achieve.

“What are you going to do if you’re a kid here? You’ve got the call centres, Bet365, debt collectors, you might start a sandwich shop if you’re lucky.”

At the jobs fair hosted by Port Vale Football Club, stallholders dismissed the suggestion there were no good jobs available for young people. One employer, who worked in the social care sector was deeply proud of the potential work on offer, boasting that her granddaughter had just started work in her industry. But they did concede that this was not the prevailing view and criticised how little work was going in to inspiring the next generation.

“Young people don’t understand the job opportunities are out there…. We used to have career advisors for every school, that’s all gone out the window.”

Gesturing around the jobs fair, she noted that many of the employers had large numbers of vacancies, which were advertised around the city. She suggested one of the biggest reasons for the lack of applications was the local transport system: Stoke’s unique geographical make up - a series of towns - leave those without access to a car reliant on buses. This renders many of the larger employers, who are invariably based outside of the city, inaccessible if the bus timetable doesn’t match up with employees shifts.

“There’s no buzz around Emma Bridgewater factory [one of the largest local employers] because no local transport will get them to be there for the start or the end of their shift, so they can’t do it. One employer in Staffordshire has had to buy people carriers to get people into their warehouse.”

Others shared this belief that poor provision of local transport is a barrier for young people. Hours after the Stoke City football match in Longton on a dark Wednesday evening, two young people who had been working as matchday staff, explained how they were waiting for a taxi as the last bus back to their town had long departed. Thankfully, one noted with a sense of relief, the club could afford to cover their taxi costs. This was a common, and for some, an expensive occurrence. Buttering toast, the café worker in Burslem explained how her son was forced to get a taxi back from his night shifts in Asda.

“My son works nights at the Asda in Tunstall, he doesn’t drive and has to get the bus there and a taxi back because the buses don’t run late.”

It was not just young people that felt local transport was not working for them. Few spoke positively about the services - arguing that, compared to other parts of the country, they had been left behind when it came to investment in their transport networks. One man was visibly emotional when voicing his frustrations. Explaining that a lack of services on Sunday to the village outside one of the towns where he lived, this meant he was forced to shell out money each weekend to pay for a taxi to visit the crematorium.

“There’s no public transport on a Sunday; costs me £16 to get a taxi return to the crematorium to lay some flowers.”

For many, public transport was expensive and cumbersome given their busy lives. For some, it was even seen as dangerous. As the café staff in Burslem explained, many people lived in the smaller towns and villages which surrounded the six towns, here there was very limited provision. A simple journey would involve multiple buses, and they would pay heavily for the privilege.

“I live a ten-minute drive away, but if I wanted to take public transport, I’d have to catch two buses to get here and that would cost me £4.”

One woman who was running a stall at the job fair, could not remember the last time she took public transport -with the exception being taking the train to Manchester or Liverpool for shopping or a day out.

“I wouldn’t bother with public transport round here, unless it’s to go shopping in one of the cites.”

A city in fear

Early afternoon in Stoke and two members of bar staff could be overheard discussing their rising bills at length. While pouring a pint, the older of the two worried about how her children keep growing and need an ever-lengthening list of shoes and school uniforms, explaining that her husband now uses spreadsheets to keep track of every penny they spend. The younger man grimaced as she talked, but quickly deferred his own fears as he punched an order into the till.

“I’m not worried yet, I put money in a meter [so I can control my spend]; I will be worrying later though.”

The study was launched to a gloomy national backdrop. News that day put inflation at over 10%, while rail strikes made travel to the city slow and cumbersome.

The cost-of-living crisis is expected to make Stoke one of the most fuel-poor parts of the country. In 2019, Stoke-on-Trent Central had 9,275 households in fuel poverty. Research from End Fuel Poverty estimates that, as of April 2022, this will rise to 18,463 - leaving 47.3% of households as ‘fuel poor’.

Stoke’s towns themselves were a picture of looming recession: high streets sparsely populated, with shoppers going about their business briskly. In Hanley, the ‘mother town’ of the six towns and the commercial centre of the local area, pound shops, discount supermarkets and fast-food chains were the only businesses enjoying a healthy level of footfall.

Despite the enduring heatwave, the atmosphere on the streets was fearful, punctured by a teenager loudly taking issue with a street preacher over the existence of God, given as she argued, life was so difficult; indicative of the frustrations felt by many.

Fear of the coming months was universal. In the kitchen at the café in Burslem, the workers drew breath at the idea of winter. They were expecting life to get extremely difficult, with one woman making clear she planned to feed her cats before herself.

“I’ve noticed the huge price jumps in petrol. I only work twenty-five hours a week; by the time I’ve paid rent and I’ve fed the cats there’s not much left; whatever is left goes on groceries.… Holidays are thing of the past. I don’t go out, don’t drink, my hobbies have had to stop.”

She was far from alone in considering cutting back on food. Further up the road, a nurse, with her young son playing at her feet, explained over tea how worried she was for the town. Despite noting how relatively better off she was than most in the area, the women conceded her son was the only one who gets “decent food” in their house.

In Hanley, the previously beaming restaurant owner instantly changed demeanor when asked how the cost-of-living crisis was impacting business. Gesturing round at the barely half-full establishment, he muttered that they now solely relied on retired people to keep the business going.

“Last week was the worst week for business in the twenty-five years we’ve been here. Less people are coming in; we’re only open four days a week now, and we’ll often close about 3pm if people stop coming in … We’re going to have to put our prices up, for the first time in four years. We’re still cheaper than Costa though.”

The impact was being felt across the city. At the youth centre evening meeting, rising costs were offered apologetically as an explanation as young adults were informed that a hoped-for trip abroad was no longer feasible. Two workers, who both lived and worked in the centre, sadly noted after the session that the cancellation would be sorely felt.

“One of the best opportunities we have seen for young people is international residencies; we’ve had to cut back on that…. Most of these young people have never had a passport, never been abroad, never been to the beach.”

Fears were not limited to the coming winter; many we spoke to simply could not see an end to the struggle. Even the idea of handouts or other interventionist measures from Government to handle the crisis were glumly accepted, with questions over how sustainable that approach could be, given that many feared the crisis may last years.

“Okay, the thing that bothers me [about handouts] what happens next year? It might get us through this year but what do we do then.”

A politically volatile city

Sitting in the backroom of a garage in Stoke, the establishment’s owner brewed the kettle with the sounds of mechanics at work in the background occasionally causing him to pause (the initial ‘five minutes max’ time commitment, long forgotten). He has voted Conservative for the last twelve years he explains, because they ‘they do more for us’ - noting that he is not typical of those from Stoke.

But even as someone who believes the Conservatives have supported Stoke over the last twelve years, and helped him and his wife do well, he is now apathetic about the state of politics and holds out little hope that the area will reap the benefits of levelling up investment.

“We are not typical for Stoke, I run this place [the garage], my wife’s got a good job, she works for a bank....[but] I’m pretty worried for them [my kids] career wise; one wants to be a teacher and one wants to work in the bank.”

Politically, much has changed in the city during that time. Stoke-On-Trent Central was held by Labour continuously from 1950 until the 2019 General Election, where the Conservatives won the seat as part of a wider trend of formerly safe Labour seats flipping to the Tories. At 69.4%, Stoke-On-Trent recorded one of country’s highest votes to leave the EU in the 2016 referendum.

Speaking to people across the six towns of Stoke - in their homes, places of work, and leisure - the sense of civic pride that people who live here feel was palpable. They take great joy from city’s rich history and community spirit. But its decline has been sorely felt, with the cost-of-living crisis seemingly turbocharging its descent.

The downward spiral has brought with it substantial political frustration towards both the Conservatives and Labour. At the pub in Burslem, there was no mistaking the anger at the state of politics. Patrons here were keenly aware of the levelling up promises made and not delivered.

“That Rishi Sunak, he came up here telling us he was going to ‘level up’, then the next day he was at a garden party down south telling everyone he wasn’t going to.”

The conversation here quickly flowed into a referendum on Boris Johnson’s premiership, with many who had voted Conservative for the first time at the 2019 general election unhappy to see him stand down. The ‘Boris’ factor was a strong motivator in people’s Conservative vote. People across the city praised his authenticity, as the nurse in Burslem put it, the former Prime Minister was a ‘human’.

“Why did we get rid of Boris? He was forced out.”

The precariousness of the Conservative support here was evident. Many people we spoke to were first time Conservative voters in 2019 and felt no love or loyalty towards the Party - citing personal affection towards Boris Johnson, or a distrust of Labour and Jeremy Corbyn, to justify their vote.

“I won’t vote Tory [at the next election], the working-class man should run this country… but I would vote for Boris Johnson”

Support for Boris Johnson was not universal among Conservative voters; some were keen to see the back of him. For them, the scandals had gone too far, and they had grown wary of the political news, with partygate still drawing an emotive reaction.

“He had to go, he was partying, you can’t do that. I didn’t break the rules, why should he?”

Strikingly, when talking politics, people in Stoke would often quickly revert to talking about Brexit. From conversations with working men in the pub in Burslem, people at the football, or shop workers in Hanley, Brexit was politics.

With a communal sense of overwhelming political apathy, their Brexit vote was for many the only politics that engaged them. They had voted for change, an improvement in their lives and surroundings, and they were still waiting to see it. While few expect it to happen, levelling up could go some way to delivering what they voted for

A garage worker at half time at the Stoke City football game summed up the collective mood. A long time Labour voter, he explained that he voted for Brexit in 2016 and then the Conservatives in 2019 because they said they would deliver it. The former he would repeat but given he had yet to see things get better, he wasn’t so sure about the latter.

“I always used to vote Labour but now I just can’t trust them. I voted for Brexit in 2016, I would vote that again, I’m not sure I’d vote Conservative again.”

With 800 days till the next election, Stoke is in a politically precarious position.

With political apathy deeply prevalent across the six towns, patience is running thin towards the levelling up promises they have heard from Government. If the Conservatives are serious about holding on to Stoke, and places like it – or Labour making a pitch to win it back that cuts through - they are running out of time to act.

All the main parties should retain a focus on levelling up. As we noted in our introduction, working-class people have finally come to understand what levelling up means – and they support it emphatically, even if they aren’t sure it’ll ever be delivered. Now is exactly the wrong time to walk away from it. As we have found elsewhere in our research (for example in our research for the Centre for Policy Studies), levelling up is becoming more important as the cost of living crisis intensifies – because, to many working-class voters, the decaying of their towns feels like their entire lives are deteriorating.

Massive economic regeneration is barely credible in the time available. So where should the political parties be focused in the next 800 days? From our trip to Stoke, and our many visits there in the recent past, four broad areas stand out for prospective policy development.

Political Policy Implications

Tackle anti-social behaviour

Stoke clearly has its problems. But it’s hard to see how meaningful progress can be made on anything without urgent action to reduce anti-social behaviour and drug use. This is completely undermining the quality of life across the towns; not only does it make the place feel unsafe, it’s clearly driving people away from visiting shops, cafes, restaurants and bars. Simply put, people in Stoke don’t feel comfortable visiting their town centres. This was the case across all demographics; there is a collective sense that these are no longer nice places to go and shop or visit for a night out. Given the expected impact of the cost-of-living crisis, this mood is likely to only worsen. The public don’t expect anti-social behaviour and drug use to disappear overnight, but they would be comforted and encouraged by a more visible police presence on their high streets, or the greater use of private security staff (which you see in cities like Derby). Seeing more security on the streets will encourage them to venture out more often and stop communities becoming further isolated in the towns.

Boost high streets

Tackling anti-social behaviour will massively help improve life. But measures to improve security must go hand-in-hand with measures to boost high streets. Across the six towns, people bemoaned the state of their high streets; the very visual nature of countless boarded up and unused shops deeply saddened them, but also practically undermined their collective prosperity. They have a strong collective desire to see these buildings utilised. The new ‘investment zones’ - effectively low-tax areas - being considered by the Truss administration present a strong economic and political opportunity to cut business rates. Doing so could help to keep open many businesses which find themselves teetering on the brink in the cost-of-living crisis – while also allowing many local people the opportunity to open a shop who otherwise cannot afford to do so (and encouraging outside investment into the city). The sight of new businesses opening on the barren high streets will go a long way in terms of demonstrating levelling up progress in the city. Furthermore, action to make it easier to convert a minority of empty shops into housing and making it easier to live above the high street would also help to bring more footfall and offer more affordable housing for young people closer to the town centres.

Encourage local heritage

Despite the area’s economic troubles, people in the city are deeply proud of where they live, While the older generations talk of the potteries, the young generations boast of the city’s parks. Investment in hotels and car parks do not give them the same sense of pride. Levelling up should not just focus on large infrastructure projects; people here want to see regeneration that actively excites them. In particular they want to see their historic buildings, which are often closed or abandoned, restored and reused. The Government finding ways to incentivize developers to renovate historic buildings, rather than simply putting up new ones, would go a long way to improving the aesthetics of city centres, and boosting people’s sense of civic pride.

Improve opportunities for young people

In less affluent cities like Stoke, people are particularly concerned about what the future holds for young people. This is partly about them being able to access good jobs. Young people in Stoke didn't want to leave the area but felt there weren't any opportunities for them if they remained. Post-16 education and skills reform at a local level continue to be a key to levelling up - ensuring that the route to successful employment doesn't mean moving away from Stoke for those young people who can't or don't want to. Government should therefore push to continue development of the lifelong loan entitlement, including more incentives for further and higher education institutions to develop flexible one or two year level 4/5 courses, with incentives for students who want to study at their local institutions. There is also a case for proposed Investment Zones to have a particular focus on young people, for example by offering tax breaks or other incentives for companies that create opportunities for under 25s specifically. But people also felt there was a major gap in things for young people to do locally, which contributed to anti-social behaviour and a loss of community feeling. The Government’s new ‘Youth Guarantee’ acknowledges this but at its current scale it is unlikely to make a noticeable difference to communities across the country. To really show it is committed to young people, the Government should commit to extending the guarantee further – so that it offers capital investment to youth clubs in every town and city and creates a tangible offer for young people and their families – for example through a voucher system that guarantees them a weekly youth activity.

Image credits

Header: Burslm Town Hall, Photo by Leonardo Zorzi on Unsplash

Stoke on Trent Station: Tim Glover, Wikimedia Commons, licensed for reuse under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.

Church Street, Stoke on Trent: Stephen McKay, Wkimedia Commons, licensed for reuse under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.

Stoke on Trent Library: Dave Bevis, Wikimedia Commons, licensed for reuse under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.

Trent and Mersey Canal, Mount Pleasant, Stoke on Trent: Roger Kidd, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.

All other images: Ed Shackle, Public First, 2022 fieldwork.