Public Attitudes to Tuition Fees

What are Labour’s options for reform?

Key Findings

1. Labour made the right decision politically on fees: Our research confirms that Labour made the right electoral decision to move away from their pledge to abolish tuition fees. It is a decision that benefits Labour significantly more than it costs them as they head towards the next general election. By 43% to 30%, respondents thought Starmer was right to go back on the pledge to abolish tuition fees. Swing voters are even more likely to think that Starmer was right, with 48% saying he was right to drop the pledge, and 28% saying he was wrong to do so.

2. Tuition fees are not a popular policy; in the abstract, there is a high level of support for fee abolition: People believe higher education is important: parents want their children to go to university, and they believe the cost is too high. They would ideally like to see fees cut or abolished entirely. This is broadly true across all demographics.

3. However, people also think that there are other, more pressing priorities for Government spending, particularly in times of financial crisis. When we asked a narrow and direct question about whether people supported fee abolition, there was widespread support, but when the question was posed differently, with people given a list of options for the Government to pursue, or when people were told how much fee cuts would cost the taxpayer, support fell away.

4. No matter how popular abolishing fees is in principle, in practice people are very against subsidising changes through general taxation. When informed of the overall cost, fee abolition is seen as too expensive, and there is little real appetite for it among voters. With the exception of raising corporation tax to pay for the abolition of fees - every other option has net negative support (more people oppose than support). It was the prospect of personal taxes and VAT rising to fund a fee cut that particularly put people off a fee cut. Hearing the scale of funding needed - and how this might need to be paid for - was a significant concern to voters.

5. People want university to be more affordable for students in the short term: Returning to maintenance grants was considered a popular alternative to the abolition of fees. Against the backdrop of the cost of living crisis, many considered the cost of the university experience as prohibitive (at least in principle). Voters are also supportive of cutting fees in certain circumstances- such as for those from low income families, or studying socially and economically important courses (such as teaching or nursing).

6. Reducing tuition fees is popular (although paying for it is not): Across the board, people think fees are too high and that people leave university with excessive debt. They would like to see tuition fees reduced, with £6,500-£7,000 being the most popular choice. In particular, people are sympathetic to the plight of young people who leave education with such high levels of debt (which most people hate), but are unsure what the alternatives are. Respondents reject the idea that fees should go up with inflation, but are supportive in the abstract of the government providing additional support when this is framed as limiting the cost increase for students.

7. There is a relatively high level of support for employers making a contribution to the higher education funding system. When described as a levy businesses pay to universities who train their workers, 59% were in support, making it a more popular choice than additional government funding. Support dropped to 39%, however, when this was framed as higher taxes employers would pay in order to hire graduates - consistent with our findings throughout that there is widespread lack of support for higher taxation in any form.

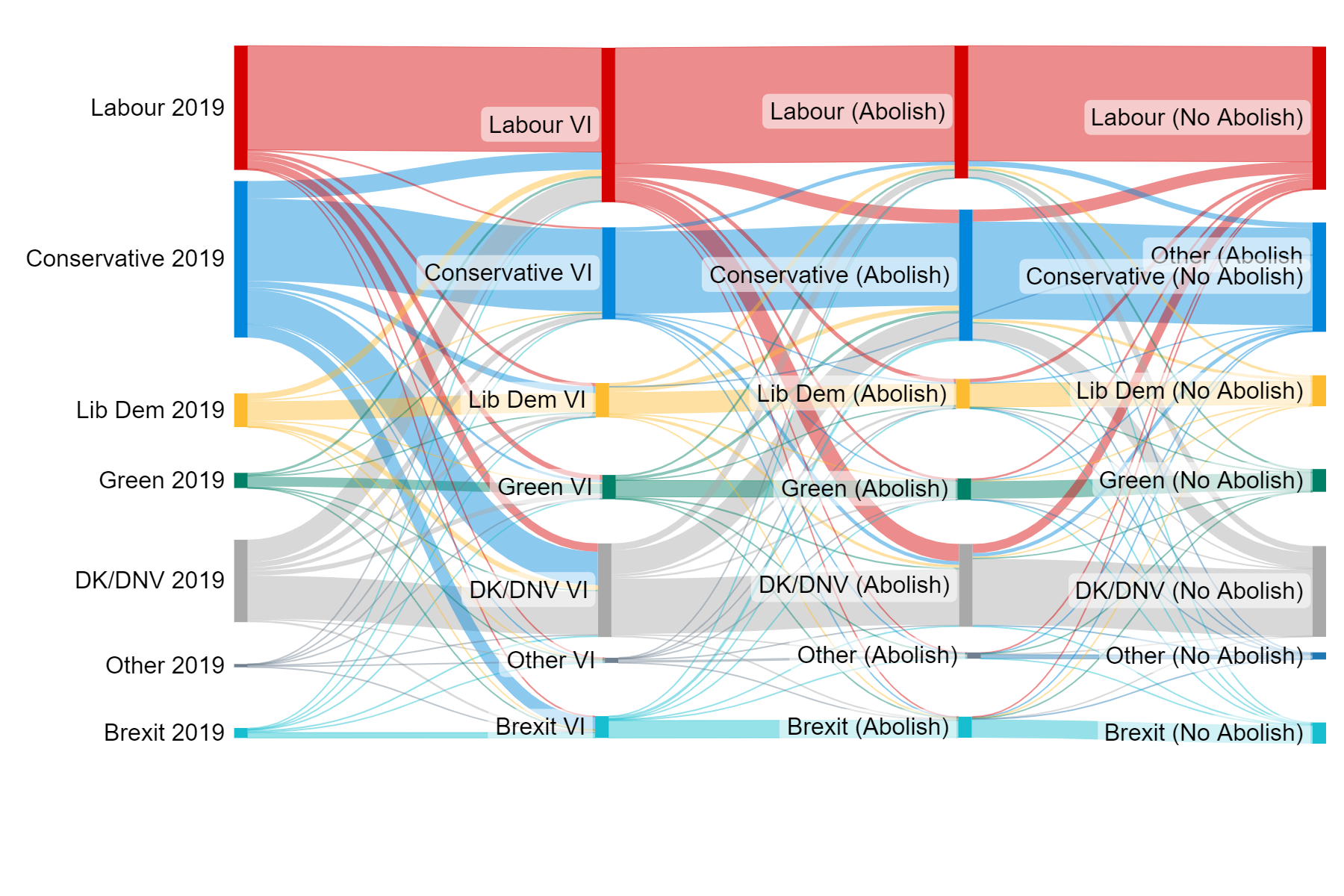

8. There are more rewards than risks for Labour when moving away from the abolishing tuition fees pledge. Abolishing or not abolishing fees has little difference on the voting intention for existing Labour voters, but is an important policy choice for undecided or swing voters. We estimate there are 83 seats in total where Keir Starmer’s decision not to abolish tuition fees significantly boosts Labour’s chance of winning the seat - including places such as Buckingham & Bletchley; both Isle of Wight seats; and Mansfield.

9. U-turning on fees may have positive electoral consequences, but it shouldn’t be shouted about. Our results suggest that dropping the pledge has a relatively minimal impact among Labour’s supporters, and if anything is assisting support among those who have switched over from the Conservatives. Labour moving away from fee abolition is likely to have positive electoral consequences, but the act of u-turning on yet another policy position should not be taken lightly. The public needs more information about the context surrounding changing policy positions, such as the impact of the economic environment on decision making and/or what that money would be spent on instead.

10. Restoring maintenance grants is the option most likely to be both a vote winner and a seat winner for Labour. It was also the option where respondents seemed content for the taxpayer to fund the commitment. When we asked voters directly if they supported reintroducing maintenance grants, assuming the extra cost would be paid for through increased taxation, 55% said they did, while just 14% said they would be opposed. 50% of respondents said they would be more likely to vote for a party which pledged to reintroduce maintenance grants, and just 8% said they would be less likely to do so.

11. Introducing a graduate tax was also more popular than abolishing fees outright, particularly amongst younger voters. Reforms to student repayments could help shore up support amongst highly educated progressives. Voters supported the idea of a graduate tax by 43% to 22%. Young voters in particular supported this most enthusiastically: 18-24s support it by 53% to 18%, and 25-34s by 50% to 22%. 36% of respondents overall said they would be more likely to vote for a party planning to introduce a graduate tax, compared to 19% who said they would be less likely.

12. There is massive, untapped support for more investment in FE. While there is widespread support for higher education in principle and practice, there is significantly more public support for further education and apprenticeships - and far more than than politicians give credit for. Politicians of all parties ought to be talking more about FE, apprenticeships and training. This is particularly true amongst swing voters, and those in target red wall seats which do not have a local higher education institution.

Background & Context

Changes to tuition fees have led to a number of significant shifts in higher education since the introduction of £1,000 annual fees in 1998. Mass expansion of higher education has been underpinned by several reforms, including the introduction of fees, their increase to £9,000 in 2010, the abolition of the student number cap, the increase in tuition fee caps for providers and changes to teaching grants and maintenance support.

Often, major changes to tuition fees policy often coincide with changes in government. The New Labour government introduction of tuition fees in 1998 and the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition tuition fee reforms in 2010 are the two most obvious. Theresa May took the opportunity after the 2017 election to launch the Augar Review, which concluded last year & established the new 40-year Plan 5 loans. Recognising the history of tuition fee policy is key to understanding current public opinion and potential responses to future changes.

Proposed changes to tuition fees have the potential to significantly impact voters' wider views of the party. Public opposition to reforms in 2010 was embodied by the student demonstrations in London, but also had an impact on voting intention: polling from Ipsos in December 2010 showed that half of Lib Dem voters were less likely to vote Lib Dem in the future because of the coalition government’s approach to tuition fees. Fieldwork carried out by YouGov in the run up to the 2017 general election found that scrapping fees was the most memorable policy in the Labour Manifesto (with 50% thinking it was a good idea, and 34% the wrong priority). BMG polling in 2017 highlighted strong public opposition to increasing the tuition fee cap to over £9,000 per year, with only 1 in 5 supporting the change.

With a general election on the horizon, along with a potential change in government and another round of media headlines about tuition fees, now is a key time for the Labour Party to understand public opinion on tuition fee reform. We believe public opinion is key to developing a strong and sustainable policy position on tuition fees in the run-up to the general election and beyond.

We therefore set out to understand the role tuition fees might play in the next general election. We wanted to gauge the salience of the issue amongst all voters - not just amongst students or recent graduates. And we wanted to test whether the decision made by Keir Stamer and the Labour Party this year to move away from the leadership contest pledge to abolish fees was the right electoral decision.

We were supported throughout to conduct this research by Progressive Britain and four leading UK universities: the University of Manchester, University of Greenwich, University of Warwick and University of York. We are grateful for their help in enabling us to carry out our work.

This report and research is the sole work of Public First, and Public First maintained editorial control throughout the project.

What does the public think about tuition fees?

"It'd be nice for the government to pay for tuition fees and everything else but it's not plausible or realistic." - 18 year old university student, Sheffield.

Tuition fees are not a popular policy, and in the abstract there is a high level of support for fee abolition.

On A Level results day this year, a poll from YouGov indicated that 32% of voters wanted tuition fees to be scrapped entirely, and a further 30% wanted them to be decreased. This finding was not a surprise.

Our poll first asked a series of questions that focused narrowly on tuition fees. In these, support for fee cuts or abolishing fees was consistently high. 45% of people agree that “university should be free for students, with the cost of their education covered by the government and paid for through general taxation”, rising to 56% of those intending to vote Labour.

48% agree that “making students pay for their university education is a bad system, as it means young people who go to university are burdened with high levels of debt.” 42% said that they thought the government should make up the difference if the cost of providing a degree went up for universities, “even if this means higher taxes or less money to spend on other issues”, compared to only 21% who wanted tuition fees paid by students to go up to cover the higher cost.

Perhaps the most persuasive of these “narrow” questions is the one showing that, by 43% to 24%, people would be more rather than less likely to vote for a political party which pledged to abolish fees. By 64% to 12%, under 25’s said they would be more likely to vote for such a party.

Had our poll focused purely on tuition fees, we would have found that people favoured cuts in fees or indeed outright abolition, that people backed this decision because the costs of HE are too high, and that Labour would secure widespread public support for embracing this approach.

But pollsters have to be careful never to beam in too closely on a particular subject area so that the subject in question no longer sits in its proper context. Polling a subject in great detail, and asking questions purely on that subject area, can throw up results which imply much greater interest, support, or opposition than might be the case in practice.

It is worth noting here that tuition fees as a policy area are not particularly well understood by the general public. In our poll, 36% of respondents said they understood student loans to the extent they could explain it to someone else; 33% felt they understood it but could not explain it. We expect that understanding in this second group is over-exaggerated: in our focus groups, participants (even some current or recent graduates) struggled to understand or explain the student loan system. There was particular confusion around whether the £9,000 figure was paid upfront, and a high level of concern about the impact and implications of future debt burden:

“I think a lot of people are put off [going to university] and are looking at other routes where you could save money, save that nine grand a year, you’ve got your house deposit there haven’t you rather than getting into crippling debt.” - 42 year old male retail manager, Exeter.

“It strikes me now that you can go for the sake of going, it’s nine grand a year minimum, £40 or £50 grand worth of debt all in by the time you’ve got loans and borrowed and done everything, and you don’t necessarily use your degree anymore” 43 year old male company director, Bristol.

“There seems to be that many different courses out there that are costing a hell of a lot of money that people are going through and accumulating debts and having student loans for. Is it really all purposeful, do employers actually see it as a value?” 42 year old male social work manager, Hartlepool

There were significant differences between different demographic groups’ responses. 37% of those in the lowest social grade (DE) said they did not understand how student loans in the UK work, compared to only 17% in the most socially advantaged (AB) group. Unsurprisingly, those with degree level education or above were much more confident than those without.

When we place abolishing fees into a wider context, rather than as a narrow issue, support for abolishing fees is revealed to be hollow.

This is particularly the case when respondents are asked to rank it against other spending priorities, and when they are told how much it costs.

Using a MaxDiff question design, where participants were shown randomly selected options for spending priorities and asked to select their preferred and least preferred options, we can position tuition fee abolition alongside other priorities.

Abolishing tuition fees for students in England was the third least popular choice. Amongst all adults, abolishing fees was behind most other options presented, including more funding for the NHS, increases in the value of the state pension, and free childcare for young children. It outranked only two policy areas: increased defence spending, and increases in the value of Universal Credit.

“Going back to the previous question about tuition fees, with the age of my kids, that's not particularly high on the priority for me at the moment. But things like the NHS, the situation there, education at primary and secondary level could obviously do with a bit of sorting out” - 43 year old father of two primary aged children, Bristol.

We note there are some clear trends on the prioritisation of tuition fee abolition among the public. Looking again at the MaxDiff question, we can see that under-25s place tuition fee abolition considerably higher, above police, pension value increases, border control and even public transport infrastructure. For those over the age of 65, tuition fee abolition was prioritised above only Universal Credit value increases.

We see a similar picture when we ask this question in the context of education spending specifically. Among a series of twelve education policy priorities, respondents ranked abolition of tuition fees ninth, with 19% selecting it as one of their top three priorities. This is significantly behind the main priorities people want to see for education spending in general - reducing class sizes by hiring more teachers (31%), free school meals for all children (31%), and higher pay for teachers and school staff (30%).

The difference in relative importance is even more substantial among swing voters - just 15% of this group placed abolition of fees as one of their top three priorities, compared to 40% who placed reducing class sizes by hiring more teachers as one of their top three priorities .

This finding was also apparent in our focus groups. Across all locations and demographics, when we asked participants what their education spending priority would be, the vast majority chose school funding - including in all of our current university student groups

“Funding (for schools) is a big thing - teachers are obviously striking because of pay…they’re not getting paid enough for what they’re really doing, they’re not paid really for the amount of work they’re actually putting into it. I think that’s a massive issue” - 21 year old male university student, Sheffield.

“I’d prioritise schools above universities, because going to university is a choice.” 28 year old female, recent graduate, Sheffield.

“Teachers definitely aren’t paid enough for the work that they do and the care and time that they put into our children” - 29 year old mother of primary aged children, Wycombe.

“When my eldest went to school, he was in a class of 30, which has a big impact on one-on-one learning. So you can get lost in the system quite easily. So my priority would be for them to reduce the (student to teacher) ratio, which obviously costs more, but it’s going to be more effective” 36 year old male IT manager, Bristol

Based on discussions across the majority of the focus groups we ran, we would speculate that this is because people believe universities are much better funded than schools - and, indeed, that universities were actually financially very well off.

This was particularly true in student groups, where the resources, facilities and teaching were significantly better in a higher education setting than in their previous school environment. Participants struggled to understand what the £9,250 tuition fee paid for, and did not understand (or felt that it was deliberately opaque) what universities spent their money on - particularly in the context of the increase in fee amount from £3000 to £9000 that occurred in 2012.

“What exactly is [the money] going on… in eight years they’ve had a six-thousand pound increase per student. You know, that’s quite a substantial amount of money to have had. Where is it going?” 32 year old female teacher, Hartlepool

“Obviously, we don’t really know enough about how much funding they do get” - 29 year old mother of primary aged children, Wycombe

“We don’t know what they’re allocating their resources for” 43 year old male retail manager, Bristol

“Universities pay so much money. Some staff earn hundreds of thousands a year. Why are they not cutting their salaries? It doesn’t make sense for a president - I don't even know what they do - why are they earning £400k or £600k. They have money for other things but still want more money.” - 24 year old female postgraduate student, Sheffield.

In the context of other, specifically post-18 education spending priorities, tuition fee abolition is similarly unpopular, and is behind lowering tuition fees for university students. As we will cover later in this report, support for apprenticeships and work-based training are the most popular post-18 education spending priorities by a large margin. Once again, swing voters are less keen on abolishing fees and more keen on other options when compared to the general population.

Fee abolition is seen as too expensive - and there is little real appetite for it among voters.

“I think if you're choosing to go into higher education, then you're the one that contributes to it. That makes sense” - 36 year old mother of primary school aged children, Wycombe.

“I don't think the taxpayer should have to pay for it. Obviously, the individual knows what they're getting. I knew what I was getting into. I just don't think [fees] should be as high as they are” - 32 year old male health and safety officer, Hartlepool

As soon as voters are exposed to different ways of paying for fees - or even just to the cost of fee abolition - support for abolition falls.

When we asked people whether they supported fee abolition without exploring the cost or potential tax implications (the ‘no context’ option), we found that 41% of people supported fee abolition, with 33% opposed. When we asked in a separate question that participants imagine a political party suggesting abolishing tuition fees would have government/taxpayers make up the difference, support dropped to 36% (with 38% opposed).

This dropped further when we asked respondents whether they supported fees with some context attached (e.g., that abolition costs £11 billion a year, or that fee abolition could be paid for by raising income tax.). The figures we used for these questions were based on Labour’s 2019 estimate of the cost of abolishing tuition fees, compared against Treasury estimates of the revenue that could be raised by different tax rise options. With the exception of raising corporation tax to pay for the abolition of fees, every other option has net negative support (where more people oppose than support).

"It’s not really fair for the taxpayer to pay for students to go to university…if they’ve already been and done it, or not gone at all, it doesn’t help them to fund it. It is a choice, and once you’ve been to uni, you’re going to get a decent paying job above minimum wage…it’s fairer on everyone” - 19 year old male, university student, Sheffield

"I don't think the taxpayer should have to pay for it. Obviously, the individual knows what they're getting. I knew what I was getting into. I just don't think [fees] should be as high as they are." 32 year-old male, health and safety officer, Hartlepool

"I think if you're choosing to go into higher education, then you're the one that contributes to it. That makes sense." 36 year-old mother of primary-age children, Wycombe

We would caution against overstating the finding on corporation tax. Voters are often in favour of raising corporation tax in the abstract as it is a tax that “they” don’t have to pay, but arguments in favour of raising corporation tax often don’t stand up in political debates against accusations of threats to ‘the economy’ and other nebulous grievances.

We also asked voters whether any of these tax changes in order to pay for fee abolition would affect how likely they are to vote for political parties. We see here that opposition to the idea does not necessarily translate into a decision not to vote for a party (in other words, opposition to a fee abolition-funding tax reform is not necessarily vote-changing). However, any of the tax rises would be vote losing, particularly among the key group of swing voters we have identified. This is covered in further detail in the next chapter.

“If someone wants to go to university to better their life, they should be supported. But it shouldn't be the case of those who didn't go to university…to then be made to pay higher tax to subsidise the minority who did actually go to university.” - 36 year old female, manager, Wimbledon.

“With the cost of living at the moment, to me, if I saw [abolishing fees] on a manifesto, I wouldn't vote for it. You know, it's the thought at the moment of my tax going up when everybody's at breaking point. It's not attractive.” - 51 year old mother of two secondary school aged children, Dudley North.

What are the political consequences of Labour's decision?

“I’m happy that Keir Starmer has got his head screwed and realised why his promises on tuition fees weren’t viable in the way he planned. On the other hand, why is another politician backtracking? Say it how it is from day one.” - 22 year old male, accounting and finance student, Birmingham.

Our research suggests that Labour have made the right decision to move away from their pledge to abolish tuition fees.

The decision to move away from the pledge received a mixed response, but by 43% to 30%, respondents thought Starmer was right to go back on the pledge to abolish tuition fees. Swing voters are even more likely to think that Starmer was right, with 48% saying he was right to drop the pledge and 28% saying he was wrong to do so. Unsurprisingly, the move is less popular with left leaning labour voters compared to those on the centre/centre right of the political spectrum.

We asked a range of questions about how people feel about Labour’s decision - most importantly, how it would affect their view of Labour, and how it would affect their decision on who to vote for.

For the majority of current Labour voters, dropping the pledge does not have an impact. For those it does have an impact on, dropping the pledge is more likely to encourage them to vote Labour than put them off.

Our results suggest that dropping the pledge has a relatively minimal impact among Labour’s supporters, and if anything is assisting support among those who have switched over from the Conservatives (though this comes at the expense of frustrating those on the left of the party.)

Dropping the pledge specifically risks votes among the parts of the Labour party which are already less positive about Keir Starmer as Labour leader. Among the group of Labour voters who say that dropping the pledge makes them less likely to vote Labour, 43% say they like the Labour party but not Keir Starmer. 50% of those intending to vote Labour at the next election, and who say they are less likely to vote Labour if the party dropped the pledge, fall on the left of the political spectrum.

The challenge is quantifying how likely these voters are to actually change their vote as a result of this change in pledge. We note that those who say it makes them less likely to vote for Labour were only slightly less likely to consider their vote “definite” earlier in the survey (50% compared to 58% of Labour’s voters generally), indicating that the move is not specifically impacting the votes of those who are already uncertain.

More promisingly for Labour, among those who voted Conservative in 2019 and now say they will vote Labour, 30% say that dropping the pledge would make them more likely to vote Labour and 11% less likely. Further, 56% of those who voted Conservative in 2019 and now say they will vote Labour believe that Keir Starmer was right to decide against the pledge, compared to 46% of those who voted Labour in 2019.

We tested the abolition fees pledge against the other policy pledges that Keir Starmer made during the 2020 Labour leadership election that had the most public support. The pledge to drop tuition fees was one of Starmer’s less popular pledges among the general public, with the third-lowest level of net support (+3%). 39% supported this pledge, while 36% opposed it.

However, this baseline support does not translate into anger at Labour dropping the pledge. Overall the issue seems to have fairly low political saliency

Of those Labour voters who said they supported the pledge, only 18% said that dropping it would make them less likely to vote Labour, 17% said more likely, 61% said their view was unchanged. On the flipside, 38% of those who opposed the pledge said it made them more likely to vote Labour.

60% of voters said his decision was unlikely to affect how they voted at the next election, with 16% saying they were more likely to vote for Starmer’s Labour and 17% saying they were less likely.

By 43% to 22%, people said they doubted this change would lose him votes at the next election; while questions of electoral prediction like this are not terribly meaningful, they do tend to act as a leading indicator of serious anger (in that people who are angry tend to assume others are angry too).

28% of all voters said they would vote for Labour regardless of what they did on tuition fees; 8% said they would only vote for Labour if they did not abolish tuition fees; and 34% said they would not vote for Labour, regardless of tuition fees. Only 10% said they would vote for Labour only if they pledged to abolish tuition fees.

This view - that tuition fees weren’t an important enough issue at this time - also came across in the focus groups.

‘If we're looking solely on those tuition fees, that's not going to make me vote one way or another… there's a whole broader [set of] issues we've got at the moment.’ - 51 year old female, accommodation manager, Dudley North.

“I think if Labour get in, there's bigger issues to sort out than this one. And they're only shifting it very slightly, so leave it as it is, and go and concentrate on the bigger issues that affect everybody because not everybody's 18, not everybody has someone who is 18. And I know that it's an investment for the future but the here and now is pretty bad.” - 42 year old teacher, mother of a primary aged child,Wimbledon.

However, we would caution that Labour’s pivot is not a cause for celebration; it is not a policy pivot that they ought to be shouting about.

Rather, it should be viewed primarily as a not-unpopular decision. It is a decision that people understand and respect within the context of a cost of living crisis and the need to spend money on other priorities.

“If they change their minds they're just like any other political party - you know, things change, external factors change. So if they could also just be a bit more transparent about what they're doing with the money instead. It's roughly like 11 billion that they're saving, you showed that earlier…Where are they putting that money? Just so we have transparency…then it would be okay.” - 24 year old, recent graduate, Sheffield.

What is harder to measure is the cumulative impact that pivoting away from a larger group of policies might have. In focus groups, people began to see the shift on fees as being part of a pattern - that politicians (including, but not limited to, Keir Starmer) could not be trusted to keep promises, and that it was a characteristic of modern politics that politicians did not stick to their pledges.

“I just think they’ll have this in their manifesto, make these promises, and they will attract the voters. And then the moment it gets tough, they take away that promise, the very thing that people would support them for?” 36 year-old female, manager, Wimbledon

“Hopefully, they won't go back on it. I think the Lib Dems said they wouldn't and then they voted to put in tuition fees, when they formed a coalition with the Conservative Party. I have voted Conservative in the past but I wouldn't again, but Labour still needs to convince me. It would convince me if they stuck to it.” 51 year-old mother of two secondary-age children, Dudley North

We gave people a range of statements testing the presence and extent of annoyance about Starmer’s decision. For the majority of Labour voters for whom dropping the pledge lessened support, the root cause of this was because they liked the tuition fee abolition policy (55%).

However, a substantial portion of this group said they did not like that Keir Starmer had gone against the pledge. 32% said they did not mind Starmer changing his mind; 29% said they did not mind the change in policy but did not like that Starmer has “gone against a pledge”; and 20% said they did not like the change in policy. Of those who plan to vote Labour, 37% did not mind Keir Starmer deciding against the pledge, but 30% did not like going against a pledge even though they did not mind the change in policy.

There are some identifiable splits in views on Labour’s overall policy making strategy.

Of those who say that dropping the abolish tuition fees pledge would make them less likely to vote Labour, 56% believe it is more important that Keir Starmer stands by the policies he ran to be leader of the Labour Party on even if some are going to lose votes.

Those who say dropping the pledge would make them more likely on the other hand have the majority view (58%) that it is more important Keir Starmer adopts policy positions that mean Labour will win the next election. The large portion of Labour voters who say the policy change has no impact tend to side with the latter (58%).

What happens at a constituency level?

In order to project our results at a constituency level we ran Multilevel Regression and Poststratification (MrP). For a number of questions, we correlate the findings with a range of demographic information, and then use this to predict the answers with the known demographic make-up of constituencies in England. We are grateful to Electoral Calculus for their support with this part of the research.

There are many caveats with questions like this, specifically:

- People over-exaggerate the impact of a single policy change, encouraging respondents to switch their vote more than they are actually likely to do in an election

- They draw increased attention to the two major parties, meaning that smaller parties suffer. In both hypotheticals, the seats where Labour received the biggest positive change in vote-share were mainly Liberal Democrat-held seats.

- Putting meat on the bones of Labour’s electoral offer, in any direction, is unlikely to have a positive impact for Labour given the high starting point of Labour’s current support. For example, a number of the seats that Labour would lose in our MrP from abolishing tuition fees are the same seats they would lose for ruling out abolishing tuition fees. The indication is that these seats are where Labour’s support in general is hollow, rather than the seats where tuition fee policy has particular cut-through.

It is also important to note that in both these scenarios the Labour offer was run up against a Conservative party counter-argument. This is likely how such a debate would play out publicly, but it does mean participants are evaluating a policy platform against a counter-argument rather than another policy platform.

We are not therefore predicting what would happen in an election, but comparing different policies at a local level to assess the importance of the issue, and the strength of feeling between different policy options

Predicting the outcome of dropping the abolishing tuition fees pledge

At the time of this polling, Labour’s lead over the Conservatives was very high, as it has been since the start of the year. As such, the estimates of electoral outcomes predicted by MrP analysis show exceptionally high Labour victories. The analysis below does not therefore represent what would happen in an actual election, but it is an indication of how policy decisions in the abstract might influence, or have influence on, voter intention.

We presented voters with a series of questions which asked them to imagine how they would vote in a general election where Labour either promised to abolish tuition fees, or ruled out MRP abolishing fees:

Our standard vote intention question showed Labour winning 463 seats to the Conservative’s 61. In the hypothetical where Labour made tuition fee abolition a big part of their campaign, Labour’s seat count fell to 284 to the Conservative’s 250. In the hypothetical where Labour rules out abolishing tuition fees, they are predicted to win in 372 seats compared to the Conservative’s 156.

In short, in both hypotheticals Labour loses support, however in the tuition fee abolition one Labour loses support in more seats.

In the hypothetical abolish tuition fees scenario, we find the biggest swings against Labour in seats they are otherwise predicted to win in Exeter East, Buckinghamshire Mid, and Beaconsfield. We find 83 seats where Labour is predicted to win when ruling out abolishing tuition fees, and lose when abolishing tuition fees. This includes several seats which are currently predicted to be heading towards substantial Labour victories, such as Buckingham & Bletchley, Bournemouth East, both Isle of Wight seats, and Mansfield.

To explain how abolishing fees impacts Labour’s position so dramatically, we can see who is changing their vote from the initial vote intention question. Labour loses 9% of their initial vote to the Conservatives, and in return the Conservatives only lose 4% to Labour. Crucially, though, 31% of those who said they were unsure how they would vote initially move their vote to the Conservatives, and only 6% to Labour. 2019 Conservatives who currently say they do not know how they would vote, returned in the majority (50%) to voting Conservative in this hypothetical.

Constituencies that are more likely to prioritise tuition fee abolition

In order to better understand constituencies where tuition fee policy might have an impact, we used a number of other questions in our MrP analysis, without the explicit tie to electoral decisions. First, directly using the prioritisation of tuition fee abolition in the MaxDiff question, which tended to be associated with younger age groups, Labour and Remain votes, student status and degree education. Our results therefore indicate, predictably, that the main areas where abolition would be prioritised are strong Labour seats with large student populations. This included Sheffield Central, Bristol Central, Manchester Rusholme, and Cambridge. With the exception of Cambridge, the seats which we would model to place the highest priority on abolishing fees are all predicted to see Labour victories by a margin of at least 20% based on current polling.

On the flip-side, those seats estimated to place the lowest priority on tuition fee abolition are electorally closer, and tend to have quite a different composition. Seats which Labour are predicted to win where we would estimate a low prioritisation of abolition include Clacton, Boston & Skegness, Exeter East & Exmouth, Ashfield and Honiton & Sidmouth.

It is worth noting that, because there is a generally limited amount of variation on the level of prioritisation by demographic groups, even in the seats which we predict to be most in favour of abolition the rate of prioritisation is relatively low. In Sheffield Central for example, which we estimate to have the highest prioritisation of all constituencies, we predict only 35% would place abolition among their top priorities, compared to 20% in Clacton which we estimate to be lowest. Even in Sheffield Central, we would anticipate a greater rate of low-prioritisation (43% placing abolition among their lowest priorities) than high.

Constituencies which are more likely to support the abstract principle of free tuition

Support for free university places in the abstract is different to prioritisation, showing greater variation by demographics in general. Again we estimate strong belief in university being free in constituencies which Labour is expected to win by a wide-margin. This includes Manchester Rusholme, Birmingham Ladywood, Bethnal Green & Stepney, Holborn & St Pancras, Liverpool Riverside and Hackney South and Shoreditch.

Constituencies which we predict are more likely to believe university should be paid for tend to be more Conservative, although there are some notable constituencies which Labour is predicted to (closely) win where this is expected to be the main position. This includes Rayleigh & Wickford, Leicestershire South, Buckinghamshire Mid, Northamptonshire South and Beaconsfield.

Taken together, our results indicate quite clearly there are more rewards than risks for Labour from moving away from the abolishing tuition fees pledge.

Abolishing fees alienates many of the voters who have moved away from the Conservatives since 2019 and upon whose support Labour’s current polling lead relies. Support for the principle of free university places tends to be higher than the prioritisation of abolition as party policy, but there is a tendency for both to be stronger among those who are already most inclined to vote Labour. When we project attitudes to a constituency level, we find that abolishing tuition fees receives support concentrated in seats which Labour is expected to win handily in 2024, but is more divisive in the seats which lean more Conservative and older where Labour is expected to have a tighter margin of victory.

What are the alternatives?

“I don't think there's any point in making a small change. Either make a big change and a big impact or don't bother at all and just leave as it is.” 32 year old female healthcare manager, Wimbledon

Testing specific alternatives to the current tuition fee system in a national level poll is not straightforward. As we’ve already noted, overall understanding of the current system is low. We therefore tested, in both the poll and the focus groups, general principles and ideas around the four main alternatives to abolishing tuition that the Labour party (or any party considering tuition fee reform) could feasibly consider.

These included:

- Changing the amount of tuition fee paid by students;

- Introducing a graduate tax;

- Reintroducing maintenance grants;

- Enabling employer/business contributions to fees.

We looked at these options in broad terms in both the poll and in focus groups. In focus groups, we also tested new options against the current system - in order to try and establish whether there was a sufficient appetite for change. We also tried where possible to look at the trade off of each policy.

The findings below do not constitute our recommendations, and further work would be required to look into each option in more depth. Rather, we wanted to see if, of the options Labour has publicly announced it is considering, if there were any immediate “quick wins” that had significant political saliency, if they were committed to a u-turn on abolishing tuition fees.

Changing the amount of tuition fee paid by students

‘I just think the fees are way too high. I don't know what they should be. I mean, 3k sounds more reasonable. But again, it does depend, I guess, on the course. I mean, should we expect our doctors to be paying £9000 pounds a year and paying all that back when they're saving lives? Probably not.’ - 36 year old female, energy sector manager, Wimbledon.

“Well, I’d want to know what the money is for. Because I liked my course, but all we got was a PowerPoint presentation. It doesn't cost a lot to put a PowerPoint up.” - 23 year old, female recent graduate, Birmingham

There was a high level support for reducing tuition fees, and near universal opposition to increasing fees. Notably, we see that there is more support for lowering tuition fees than both a) keeping them at their current level of £9,250 and b) outright fee abolition.

63% say tuition fees are too high, compared to just 3% who say they are too low (with 18% saying they are at about the right level). When told that a university education costs more than £27,000 for tuition alone, 43% said it should cost much less than this, and a further 27% said it should cost less than this. Labour voters were more likely than Conservative voters to think tuition fees should cost less overall (82% to 60%). 64% agree with the statement that that “currently there are some people in England who are unable to go to university, even if they want to and get the grades to do so, because of the costs”.

This came across both in the polling and in focus groups - most strongly amongst those from lower income of financially precarious households.

“I think that - for want of a better word - they are pricing people on a lower bracket of income out of universities, it's becoming something that is an elite programme for people with money to attend. Education should be free for all, everybody should have access to it.” - 52 year old mother of two secondary aged children, Hartlepool.

“When the government did pay, it was based on ability, it meant that you were tested on your ability to achieve that degree. So those in more deprived backgrounds, if they were intelligent, then it wouldn't be dependent on how much mum and dad had or didn't have. Whereas now I think there's a steer towards it's a money making business rather than education.” - 48 year old mother of one secondary aged child, Exeter.

“[University] should be funded better from, like, the government. I think it’s just a money making thing, isn’t it, really. It’s just easy to put it on students and get a load of money off them instead.” 32 year old male health and safety officer, Hartlepool

The view that the cost of university is too high was felt across Conservative voters (51%) and Labour voters (73%), although more pronounced among Labour voters. As we might expect from the groups, a majority of those who felt the current fee level was too low or about right (52%) describe themselves as relatively or very financially comfortable compared to 41% of those who feel fees are too high.

We tested levels and support and opposition for different fee levels across our poll. As already established, abolishing fees was the most politically divisive option. On aggregate, reducing fees to around £6,000 - £7,500 received the highest net support, and was more popular than abolishing fees outright. Increasing fees was strongly and universally opposed. When we asked directly whether tuition fees should increase with inflation, 50% said that they should remain fixed, and a further 19% said that they should rise below the rate of inflation.

Different groups do show peaks in support at different suggested price points. For example, 18-24 year olds show very strong levels of support for all proposed reductions, including abolition, which then drops rapidly at the suggestion of keeping tuition fees at their current £9,250. Those aged 65 and over on the other hand are divided on reductions to £6,000 and £7,500, peak in support for keeping fees as they are, and show opposition to both increased fees and abolition.

Crucially for Labour ahead of the next election, the voters who have moved from Conservative 2019 voters to planning to vote Labour are divided on abolishing fees, but show a peak in support for suggestions to reduce fees to £6,000. Those who voted Conservative in 2019 but are now unsure how they would vote are more difficult to please, only showing support for the suggestion to keep fees as they are now, but as with every group showing the lowest support for suggestions to increase fees.

The reason there is such widespread support for a fee cut is because of near-universal understanding that higher education is extremely expensive, and that students leave with very large debts. Overwhelmingly, people think education is too expensive and should be reduced, even if they ultimately balk at the options for financing higher education in different ways.

“It just seems very expensive…compared to what it used to be, in the past it used to be two or three grand a year, then they increased it to 9 grand, and it’s an extremely big jump” - 28 year old female, recent graduate, now working as a teaching assistant, Sheffield.

‘I didn't go to university myself, but I know the fees are extortionate. - 36 year old female, energy sector manager, Wimbledon.

We tested whether this opinion held when respondents were introduced to some of the consequences of a straight fee cut - namely, that the number of places available for students may decrease. Here, support for the “status quo” - £9,250 fees - performed slightly better, but was still not as popular as a fee cut. 37% of respondents wanted fewer people going to university if it meant that the costs were reduced for students. There was little difference in responses between those intending to vote Conservative or Labour.

We also tested whether there was support for reducing fees in more specific circumstances. Using a MaxDiff question design, respondents were shown a series of options for fee changes and asked to select the one they would most and least like to see. Introducing a progressive system of tuition fees, where students from lower income families pay less in tuition fees than those from higher-income families, was considered the most popular tuition fees policy (with a net score of +19%).

Targeted reduction of fees for courses in high demand was also popular, with a net score of +18% in the MaxDiff analysis. In the support/oppose questions, we phrased this slightly differently, asking people if they supported fee reductions for economically important subjects (which they did, by 54% to 14%) and for socially important subjects (49% were in support, with 19% opposed).

For Conservative 2019 voters who now said they would vote Labour the prioritisation of these options was broadly the same, with the progressive fees and lower fees for high demand subjects top performing options. Relative to the country as a whole, the abolish fees option performed more poorly among this group, falling to the second lowest priority after increased fees for home students.

When we asked a straight support/oppose question about whether fee reduction should be targeted at students from lower-income households, levels of support were also high, with 64% in support and only 11% opposed. 55% of those opposed voted Conservative in 2019, but support for this question was consistently in the majority across key voter groups. Those who had switched from Conservative to Labour since 2019 supported the suggestion by 66% to 15%, those who had stayed with the Conservatives by 54% to 19%, and those 2019 Conservative voters who were now unsure by 56% to 14%.

In focus groups, views were slightly more nuanced: they did not want to see lower fees for high-paying professions, but did more strongly support fee reductions for public sector roles such as nursing, teaching and social work.

They want them (nurses) to go through a course where they’re paying £9,000 a year to go into a job that the country knows they’re not getting paid enough to do….if you want the NHS to continue, I don’t think future generations are going to want to go into education for a job like this.” 26 year old male, recent university graduate, Sheffield

“If you’re putting back into the community, especially if you’re working in the NHS… I think there should be some sort of support there for that.” 32 year old female teacher, Hartlepool

Introducing a graduate tax

A graduate tax has long been proposed as an alternative funding and repayment system to tuition fees. It was one of the options modelled in the work by London Economics, HEPI and University of the Arts London earlier in the year as a potentially fiscally neutral way to reform higher education funding. It is also a way for Labour to “abolish” tuition fees without passing the cost of such an action back onto the taxpayer - something we have already established is an unpopular political move.

Despite widespread opposition to taxes in general - and higher taxes specifically - in other areas of the poll, voters supported the idea of a graduate tax by 43% to 22%. Young voters in particular supported this most enthusiastically: 18-24 year olds support it by 53% to 18% and 25-34s by 50% to 22%. Among those who voted Conservative in 2019 and now say they will vote Labour there is also support, with 50% in support and 21% in opposition. The suggestion sees support among those among Labour’s voters who position themselves on the left (49% support) and the centre and right (49% support).

We then followed up our questions about support for a graduate tax by asking whether a party proposing to introduce a graduate tax would affect someone’s likelihood of voting for a political party. In contrast with what we found if a party were to propose fee abolition, we find that proposals to introduce a graduate tax are more of a vote winner than a vote loser, at least in theory.

36% of respondents said they would be more likely to vote for a party planning to introduce a graduate tax, compared to 19% who said they would be less likely. Among swing voters, 30% said they would be more likely to vote for a party in this scenario, and 24% said they would be less likely to vote for a party in this scenario. The option was also popular amongst younger voters; under 25s say they would be more likely to support such a party by 49% to 16%, and young graduates 45% to 21%.

The proposal for a graduate tax received support across Labour’s base, but particularly among younger and degree-educated voters. The only risk our poll highlights is that many feel neutral towards this suggestion, likely indicating some uncertainty about how exactly the policy works (although note, we did provide an explanation).

In our focus groups, the graduate tax was most popular amongst current students and recent graduates - and strongly preferred to both abolishing fees, and the current student finance system. When asked to pick between two “blind” options - one depicting abolishing fees, and one introducing a graduate tax - nearly all our student participants chose the graduate tax option, believing it to be a fairer system both for themselves and for the taxpayer more broadly.

“It shouldn't matter what you think, like the student loan debt isn't really debt. So it wouldn't really matter what they say it was because it'd be easier if they just turned it into a levy like, that's what it is essentially anyway, you pay 9% of what you earn. Because you're a graduate it's just like a graduate tax is how you should look at it really.” - 22 year old male, accounting and finance student Birmingham

Reintroducing maintenance grants

“You need to be able to try your best to give as many to those who are disadvantaged as possible.” - 29 year old male, project manager, Wimbledon.

Restoring maintenance grants is the option most likely to be both a vote winner and a seat winner for Labour

Reintroducing maintenance grants for poorer students is popular with voters, and was seen as a greater priority than the abolition of tuition fees themselves. It was also supported more universally in both the polling and focus group - particularly compared to a grad tax, which was only really enthusiastically supported by younger respondents who had experienced the current student finance system.

When compared to other proposals for post-18 education spending (above), restoring maintenance grants was the third and fourth-most popular option, depending on how you propose to pay for it.

We gave respondents two hypothetical options and found there was more support for reintroducing maintenance grants through general taxation than there was for funding a return to grants through increased tuition fees.

When we asked voters directly if they supported reintroducing maintenance grants, assuming the extra cost would be paid for through increased taxation, 55% said they did, while just 14% said they would be opposed. 50% of respondents said they would be more likely to vote for a party which pledged to reintroduce maintenance grants, and just 8% said they would be less likely to do so.

Among those who have switched from Conservative 2019 to Labour, we see high support for this proposal: by 55% to 13%, they say this would make them more likely to support a political party. Within Labour’s voter base there is a slight age trend (70% of 18-24 Labour voters say it makes them more likely to support, 54% of 65+ Labour voters), but among all age groups the proposal sees majority support. While the proposal is more motivating for Labour-voting graduates (69%) than non-graduates (58%), this is largely driven by no-impact among non-graduates rather than opposition.

Both options which included maintenance grants for poorest students - paid for both through increased taxation or through increasing tuition fees for students were popular in our MaxDiff analysis of options for tuition fee policy. This is the only time in our poll or focus groups that increasing tuition fees was an publicly acceptable option - showing the strength of support behind reintroducing grants.

Maintenance grants were well received in focus groups, as many were keen to see more support for current students given the cost of living crisis.

“I think when the government did pay, it was based on ability, it meant that you were tested on your ability to achieve that degree. So those in more deprived backgrounds, if they were intelligent, then it wouldn't be dependent on how much mum and dad had or didn't have. Whereas now I think there's a steer towards it's a money making business rather than education.” - 48 year old mother of a secondary aged child, Banker, Exeter.

In student groups, and among those with middle-class parents, there was some concern about the narrow targeted allocation of maintenance grants to just the poorest households, with some worried that students who needed support would still miss out on it. These respondents wanted to see a broad grant system that supported a wider (rather than a narrower) range of students. This is the only time in this research that we saw widespread support for a policy commitment that would require significant spending, highlighting the overall popularity of restoring maintenance grants as a higher education policy option.

“I don't like the fact where it says, in option two, that the poorest households receive a maintenance grant, just because…I just think that could not always work out fair.” - 36 year old, mother of primary school aged children, Wycombe.

Graduate Tax vs. Maintenance Grants?

We didn’t model every option at a constituency level, but we did compare the relative popularity of replacing the current fee system with graduate tax, and the relative popularity of reintroducing maintenance grants. We asked respondents whether they would be more or less likely to vote for a political party that promised to do either option in an election, and using MrP predicted these for each constituency. Of course, these two proposals are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and they were not presented in that way to respondents.

We find the graduate taxes are less variable by constituency, with support ranging from a predicted 33% to 47%. Correlating particularly with age, education and Labour vote, we find graduate taxes see high support in strongly Labour urban seats like East Ham, Birmingham Ladywood, and Bethnal Green & Stepney. Support is lower among seats which are expected to stay with the Conservatives in general, but Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire Mid and Honiton & Sidmouth are notable exceptions. Even in these seats, we project that graduate taxes are likely to motivate voters rather than lose them, with an estimated third more likely to vote for party proposing it and 21% less likely to. Again, we note the high proportion who feel it would not impact their vote.

For maintenance grants we predict strong support across all constituencies, ranging from a minimum of 41% to 66%. We find some correlation between support here and proximity to University, which means our estimates of strongest support levels again feature the expected Labour seats in student areas like Bristol Central, Sheffield Central, Headingley, Manchester Rusholme and Liverpool Riverside.

Contributions from employers

“There were a number of things I hoped to be able to achieve and wasn’t able to achieve; I would have liked to see employers contributing by paying more NI if they employed a graduate … There are three beneficiaries from university education:.... In my time the individual and the State were contributing but not the employer and we should revisit that.” - Charles Clarke on his time as Secretary of State for Education and Skills (2002 - 2004)

We also wanted to test public appetite towards employers contributing to the higher education system - proposing a tripartite model in which the student, state, and employers would contribute towards the higher education funding model. We did not test voter intention for this option - but wanted to assess baseline support or opposition.

We framed this as proposals designed to increase the available funds to universities - but which maintained fees at their current level. In this scenario, employer contributions could be used to “plug the gap” between the current below-inflationary unit of resource without needing to rely on increased funding from the taxpayer via the teaching grant or other mechanism.

This idea was popular in focus groups - occasionally coming up unprompted. Some suggested that employers, in particular large ones, should support students if they are benefitting from their skills.

“There's enough philanthropy in this country really: say, you’ve got Microsoft, you’ve got Apple, you've got Jaguar Land Rover and so forth. They could actually fund talented people to go to university at no cost.” - 60 year old, father of college aged student, Dudley North.

“Leading businesses and enterprises should be engaged in universities to kind of nurture and develop kind of leading talent…. rather than just relying on, you know, the taxpayer pair entirely” - 50 year old, male, parent of secondary aged children, Wycombe.

In our poll, there was a high degree of support for employers' contribution to the HE funding system - more so than additional government funding. Support jumped 20 percentage points from 39% to 59% if this was framed as a levy paid by businesses to universities who train their workforce, rather than as a higher tax paid as businesses in order for them to hire graduates.

Lowering fees for students through increasing employer contributions was also the 5th most popular option in our MaxDiff analysis - tied with introducing a graduate tax, and ahead of lowering fees paid for through general taxation

What about the rest of the tertiary education system?

“I always thought I’d want my children to go to university…but now I’d be perfectly happy if they said 'I’m going to learn a trade.' I don't think university equals success anymore. I went to university and I never used my degree.” - 41 year old mother of two primary and secondary aged children, Bristol.

One of the consistent findings of this work, and previous work establishing public attitudes to higher education, is that there is a high level of support for higher education. Across all demographics, people see the value of higher education - both to individuals and to the country as a whole. The scepticism about the value of degrees you sometimes hear about in parts of the media and politics is rarely shared in the public.

“I would love my children or to go to university, I think it's just, it's an opportunity that me and my father didn't have. So that's one thing that I've always said to the children, you know, education is something nobody can take away from you, so it's a skill that you'll always have.” 52 year old female school office manager, Hartlepool

66% of parents who have a child aged 16-18 would probably or definitely want their child to go to University, including 79% of parents who themselves went to University and 58% of those who did not. Similarly for those with children under 16, 69% would want them to attend University.

46% believe that students should study a subject they enjoy, rather than the one that would boost their career prospects or earning potential (44%) - though we note this is a view shared more by younger respondents than older.

Regardless of background, most people aspire to university on behalf of themselves or their family. This view is, however, complemented with a general view that too many people go to university. There is some nuance to this; when we ask in general whether too many or too few people go to university today, a plurality (42%) say too many, However when we inform people that around 50% of school leavers pursue HE a plurality say this is about the right amount (42%) and just 29% say this is too high.

As a result of this, we find that people tend to prioritise the affordability of University over the attendance. 55% of the English public say it is more important for the Government to focus on reducing how much it costs for people to go to University, than increasing the number of people who go to University. This rises to 60% of those planning to vote Labour, and 65% of graduates who are planning to vote Labour.

Generally, we find that this view that too many people attend university comes from a belief that not everyone should feel they have to go to university, and a desire for viable alternatives. Our polling found, as an example, that 58% of those who say too many people are going to university place more apprenticeships for over-18s among their priorities for HE spending.

Taking this last point, our research revealed there is massive, untapped public support for more investment in FE. We did not set out with a research question to compare support for FE vs. HE. Throughout both the poll and focus groups, however, we found very high levels of support for vocational training, particularly apprenticeships, and a frustration that there was so much focus on higher education amongst politicians.

“I feel as if work experience is in demand. So if you're coming out of uni at 26, and you've got all the qualifications, but no work experience, somebody that started from the bottom and worked their way up, literally doing the job , they move faster, they get to where they want to be quicker, and then they don't have the debt as well.” - 35 year old mother of a secondary aged child, Dudley North.

In our polling, vocational options, such as more apprenticeships offered to 18-year olds (48%) and more funding for training courses for working-age adults (34%) perform significantly better than other tertiary education policies - including restoring maintenance grants and lowering tuition fees.

Broadly speaking, our research suggests that enabling more people to access apprenticeships (if they wish to) would be positively received by many.

“I was brought up and told you have to go to college, you have to go to university, you have to get a degree if you want to get anywhere in life was what my parents used to say, but now, you don’t necessarily need a degree at all to do what you want to do or do well” 46 year old male retail manager, Bristol

Crucially for Labour, enabling apprenticeships plays well with key voter groups. 52% of those who voted Conservative in 2019 and now intend to vote Labour place it among their priorities for over-18 education funding, as do 59% of 2019 Conservatives who now don’t know. In a direct trade-off, 67% of the public say that we need more people in FE colleges for vocational skills compared to 20% saying we need more in University. Among Labour voters, 60% have this view, but among those who have switched from the Conservatives 72% do, and among those Conservatives unsure of their vote 80% hold the view.

In our focus groups, there was overwhelming support for apprenticeships both before and during discussions focussed on tuition fees. Boosting the number of apprenticeships came up in every single group - although discussions were particularly prominent in groups with social grade C2D parents. Positive sentiment towards apprenticeships was largely driven by an aversion to long term debt and overall cost of higher education - with apprenticeships seen as a more cost effective option to achieve the same quality of education and career prospects.

“[My son] is now starting to change his mind that actually what he'd rather do is do an apprenticeship or some sort of scheme like that, and I couldn't think of anything better based on how the system works now, because the thought of just coming out of higher education with a giant debt, when you can actually go and get the same qualifications and get paid and make progress in a company at the same time.” - 49 year old father of a secondary aged student, Wycombe.

“My view has changed, I was brought up, you know, you have to go to college, you have to go to university, you have to get a degree if you want to get anywhere in life my parents used to say. But what my opinion now is, no, you don't necessarily need a degree at all to do what you want to do or do well in life.” - 46 year old father of two secondary aged children, Bristol.

While there is very widespread support for higher education in principle and practice, there is significantly more public support for further education and apprenticeships - and far more than than politicians give credit for. Politicians of all parties would do well to be talking more about FE, apprenticeships and training.

Methodology

Due to the different nature of higher education funding in devolved nations, our research focuses on individuals living and studying in England only .

To gather evidence for this report, Public First conducted the following research activities:

1. An anonymous, online survey of 8,333 adults across England from 19th May - 31st May 2023. All results are weighted using Iterative Proportional Fitting, or 'Raking'. The results are weighted by interlocking age & gender, region, and social grade to Nationally Representative Proportions. Some of the data collected from this survey was also subjected to Multilevel Regression with Poststratification analysis (MRP) in order to predict attitudes at the constituency level in England, carried out by Electoral Calculus. Data tables are available on our website

2. 8 focus groups of between 6 and 8 participants recruited from areas identified from the MRP analysis as being vital in understanding variations of opinion in regard to tuition fees. All focus group participants were considering voting for Labour at the next general election, even if they had not done so previously, but many had not yet made up their mind. Demographics for the group were aligned with key target voters for the Labour party, as well as being in key electoral seats identified in our MRP analysis.

Parents in social grade C2D who voted Conservative in the 2019 General Election, who were currently undecided who to vote for but considering voting Labour in the next, living in:

Hartlepool - a constituency in the red wall which has no nearby university and has a large population of people educated below degree level

Dudley North - a constituency in the Red Wall which has no nearby university and has a large population of people educated below degree level

Wycombe - a traditionally Conservative seat with a high number of working and lower-middle-class parents

Parents in social grade ABC1 who were undecided who to vote for and were considering voting Labour, living in:

Exeter - an area with a seat identified as having the biggest swing away from Labour if fee abolition were to take place

Wimbledon - an area with a marginal seat where abolishing fees was a high priority and a graduate tax was also popular

Bristol - an area with strong universities and high levels of university participation.

Current undergraduate students paying home tuition fees who either voted Labour in the 2019 General Election or intend to in the next:

Sheffield Hallam - a marginal seat where abolishing fees was a high priority but with the highest potential to swing to Labour when ruling out abolition

Birmingham - an area with multiple seats that consider student numbers a higher priority than fee abolition, although still supportive of abolition